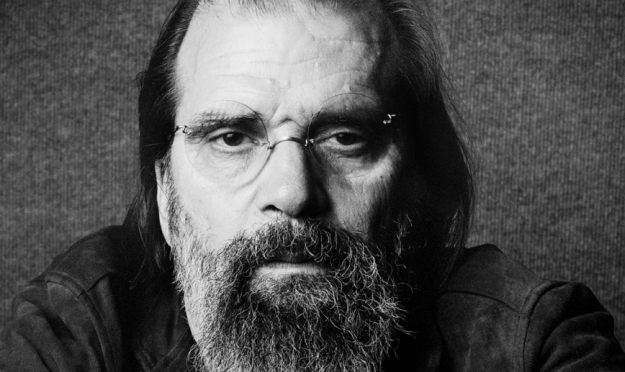

Steve Earle’s old friend has always been the blues, but never has the prolific and mercurial songwriter released a quote unquote blues album. But that will change on February 17 with the arrival of Terraplane Blues, an album that takes its name from the Robert Johnson song about fast cars and even faster women.

Earle, who currently resides in New York City, cut the record this fall in Nashville at House of Blues studios over a 6-day stretch with his band the Dukes. It’s a bit of a breakup album, he says, what with it coming on the heels of his recent split with singer-songwriter Allison Moorer. Terraplane is a raw and dirty affair sonically, and moves from acoustic East Texas blues numbers to boogie-rock to early Stones-type ballads, with one spoken-word piece in iambic pentameter thrown in for good measure. The record was produced by R.S. Field and is being released by New West Records.

We hung out with Earle in the studio and chatted about the album, and a host of other topics, including the Shakespeare authorship controversy, where Elvis really learned how to “shake it,” and why Earle’s writing songs for ABC’s Nashville.

So how long have you been thinking about making a blues album?

For a while.

I’d thought about doing it at some point as long as seven or eight years ago. I basically had a couple of things going. I wrote some songs that aren’t on this record, and they were sort of headed in one direction, and then the blues songs started to come along. And I don’t know why, but I decided that I’d make a blues record and then I’d make a country record, so that’s what I’m going to do. The country record’s like half-written. And some of the stuff [on the country record] I wrote for Nashville, just because T-Bone [Burnett] asked me to.

The TV show?

Yeah.

Now when I think of Steve Earle making a blues album, I think of the Mance Lipscomb, Lightnin’ Hopkins kind of stuff.

That’s there, but I decided on the Mance thing – there’s a Mance thing and a Lightnin’ thing. You know, Lightnin’ played with a band whenever he could. Mance didn’t, but I don’t think it was a choice. What Mance really did was he played dance music on one guitar when he first started out. So we did a thing that’s very much Mance, but we did it with a band. It’s all acoustic. You know, I’m playing guitar and Chris [Masterson] was playing a baritone resonator. I think that’s what he’s playing. We’ll get drums on it, and upright bass. It’s very much the kind of thing Mance did, the sort of in-between blues and ragtime. I mean, there’s no such thing as between blues and ragtime. There are people that, most of them wearing bowling shirts, will probably listen to this record and say that some of it’s not the blues. But they would be mistaken.

And “Tipitina” is the blues. It’s the 16-bar blues. And pre-war “St. James Infirmary” is the blues. So that stuff’s included. There’s a boogie. I chose Canned Heat rather than ZZ Top for that path. But there’s one song that’s based on the fact that I very much believe, for me, where I come from, the first two ZZ Top records are blues records. And that one track that rocks pretty hard is kind of from that.

So is “Terraplane Blues” your favorite Robert Johnson tune?

No, my favorite Robert Johnson tune is probably “From Four Until Late.” “Terraplane” just seemed like a good title. It’s a car. It’s a fast car. I’ve never wanted to learn how to play “Terraplane,” and I don’t know for sure if I will do it. I’m trying to figure if I can do it. It’s a hard song to sing, so I gotta find some version of it that works for me. [If I do record it], it’ll be an extra track. You have to have an extra track or two.

I know you’re a big patron of Matt Umanov’s guitars in Greenwich Village.

I’m a big patron of guitar shops in general.

I understand you’re friends with Zeke Schein who works there. He’s a big Robert Johnson guy.

Zeke knows more about this stuff than anybody that I know. I spent hours talking to him about this record. He knows what tuning all the songs are in. Zeke’s a really good player. He plays all that shit.

Do you think the general perception of blues these days is that it was just a form of folk music and that the dance element and the popular element of what blues used to be in the ‘30s and ‘40s has gotten lost?

Yeah, I mean that’s one thing – this record’s got a song that’s sort of based on “Smoke Stack Lightning.” And “Smoke Stack” – all those Chess records were jukebox records. They were made for people to dance to. They weren’t long and there wasn’t a lot of improvisation on them. They were improvising, but there wasn’t a shitload of long solos because they wrote two minute and 30 second records. And that’s represented here. But it very much sounds like this band. It’s the best band I’ve ever had. The existence of the band was part of the inspiration for making the record. Finally doing it had as much to do with Chris being in the band as anything else because I never had the guitar player to do it.

Did your time in New Orleans working on HBO’s Treme inform this album?

Absolutely.

It wasn’t until recently that I learned that “My Bucket’s Got A Hole In It” was actually taught to Hank Williams by that blues musician who’s from New Orleans.

“Tee Tot” [Rufus Payne] is the story … I don’t know how much there is [to all that] … there’s all those stories about how black music and white music … I don’t know. The legend says that Elvis got all those moves from watching black gospel groups and watching bands on Beale Street. I know where he got everything he got. It was from Wally Fowler. Wally Fowler was the founder of the Oak Ridge Boys. He was the first white gospel singer to perform the way that black gospel groups did. You know, to not just stand there. He was the first real showman in white gospel music and he founded the Oak Ridge Boys. And there’s been an Oak Ridge Boys ever since.

When Guitar Town was written I was writing for Sunberry/Dunbar, which belonged to the Oak Ridge Boys and was run by my publisher, Noel Fox, who was the last bass singer in a non-secular version of the Oak Ridge Boys. Oak Ridge Boys are a gospel group. And [Richard] Sterban took over. Sterban came from J.D. Sumner, who replaced Noel because Noel quit. Noel went out and worked for Olan Mills or something, you know, selling people pictures of themselves for years. When the Oaks got big they brought Noel back to run their publishing company. He was a great song man. He’s gone now, but there would be no Guitar Town without Noel. He told me to write an album and not worry whether or not it would get you a record deal, and I had just lost my first record deal after being here for 12 or 13 years. I was pretty discouraged, and didn’t have much faith in myself as a writer anymore. And I wrote the songs that became Guitar Town in about 11 months.

But I heard all the war stories from him and from the Oaks and from those guys during that period, and they set me straight on where Elvis got that shit, and I believe it’s true. It just makes more sense. I went back and found a couple of films of Wally Fowler performing and [I was like] “ohhh …”

But it took a while to get poor white people and poor black people at each other’s throats, and it didn’t always take. There was already someone who was interested, like upper middle class kids like Sam Phillips slummin’ just because they loved the music. He ended up starting Sun Records, that kind of stuff. So you know, it couldn’t stay contained forever, the two things. And Sam knew, and that’s not a legend. He looked for years and [said], “If I can find a white kid, a good looking white kid who can sing this stuff, then I’m going to get rich.” He didn’t get as rich as he should have, but he got rich.

You’ve got a history of borrowing from the blues lexicon in your own tunes. And you taught that course at the Old Town School of Folk Music years ago, I think it was titled “The Cool Shit To Steal.” How do you walk that line between borrowing from traditional material and coming up with original stuff? You know, so much of the folk tradition is obviously about borrowing.

It is, but in the blues it’s really tricky because it’s a limited genre. Some of this stuff is definitely post-Bob Dylan blues. Dylan started making blues records on purpose a long time ago. It begins on Bringing It All Back Home and it’s fully realized on Highway 61. Everything is in a blues form from that point on for a while, until probably Nashville Skyline or John Wesley Harding maybe. And I thought that it would be sort of fun to do something where I didn’t necessarily have to come up with a lot of melodies, that I would find at least the components for the melodies in this toolbox that’s called the blues.

Some of it’s more original that I thought it would be, melodically. The lyrics I pushed as hard as I’ve ever pushed. Some of the best lyrics I’ve ever written are on this record. I wrote a spoken word piece in iambic pentameter again. That’s me making up for my lack of education. I didn’t get a chance to write in iambic pentameter in high school because I only got halfway through the 9th grade.

So are you still a big Shakespeare buff?

Yeah. I don’t think that the glovemaker’s son wrote those plays, but yeah. I think Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, wrote them. So does the greatest Shakespearean actor of our time, so did Mark Twain, so does Meryl Streep.

I don’t know if I believe that. Is there evidence?

There’s tons of evidence. There’s evidence both ways. You should read all the books and make up your own mind about it. There’s no way it was a bunch of people. It was one person, in my mind, and it pisses Billy Bragg off because he thinks I’m being elitist, and I’m far from an elitist.

There’s no way [it was] someone who’d never been to Italy, was illiterate, or in other words couldn’t form words, and that’s probably true of Shakespeare and most actors of his time. He could read but he couldn’t write, because that was a much harder thing to learn to do then. He had no intimate knowledge of life at court, and didn’t have political protection to keep him from getting his fucking head chopped off with some of the things he was parodying and some of the things he was writing about when he was writing them.

So the theory about de Vere is that he was either Elizabeth’s son or Elizabeth’s lover. Some people even think both. My guess is that he was her son, or somehow related to her, anyway. And so he got away with it. But it’s one person, it’s a singular genius voice. There’s no way it was more than one person, no way there was more than one person that brilliant in Elizabethan England, when there were only a 100,000 people in London and the whole area. It just doesn’t make sense.

Like with Marlowe and Ben Jonson. Their voices were so different from the Shakespeare plays, there’s just no way …

Yeah, and Ben Jonson is where a lot of the clues that it may have been de Vere come from. Ben Jonson wrote the preface to the First Folio, he’s the one who called him “The Soul Of The Age” and all that stuff. And they all were writing really great stuff, but nobody was writing anything like that. And nobody really emulated him in his time. Shortly after he died people did. And he became a big deal – Shakespeare’s plays were being staged and they were hits in London. And at that moment Elizabeth was patronizing theater. She didn’t go out to the theater, she couldn’t do that, but plays were brought in and performed at court. And she was the very first monarch in Europe that did that, which is another clue.

But there are a lot of books about it, and there’s a lot of evidence, and people are horrified of it. There’s a film called Anonymous that’s about the authorship and it’s just a shoot-em-up. Every theory is about Edward de Vere being the actual William Shakespeare, and who the real William Shakespeare was, and why he got set up. I think it’s really simple. I think he had to have a front because he was the Earl of Oxford and he couldn’t be a playwright, so I think he just set up a guy and paid him, because Shakespeare retired and went back to his hometown and set himself up in a wool business and fucking sold wool for the rest of his life after becoming the greatest playwright and actor of his age. It just doesn’t make sense.

He was a hoarder too; he hoarded grain during the plague, which was a bad thing to do.

Yeah, he was a businessman. That’s what he was. He was a Republican. But yeah, I believe that.

(American Songwriter, April 2015)