From American Songwriter interview, 2013.

Joan Baez epitomizes the ideal of the American folk singer. Ever since rising to national prominence in the early ‘60s, she’s stood at the crossroads of music and social protest, adhering firmly to the belief that music can in fact change the world.

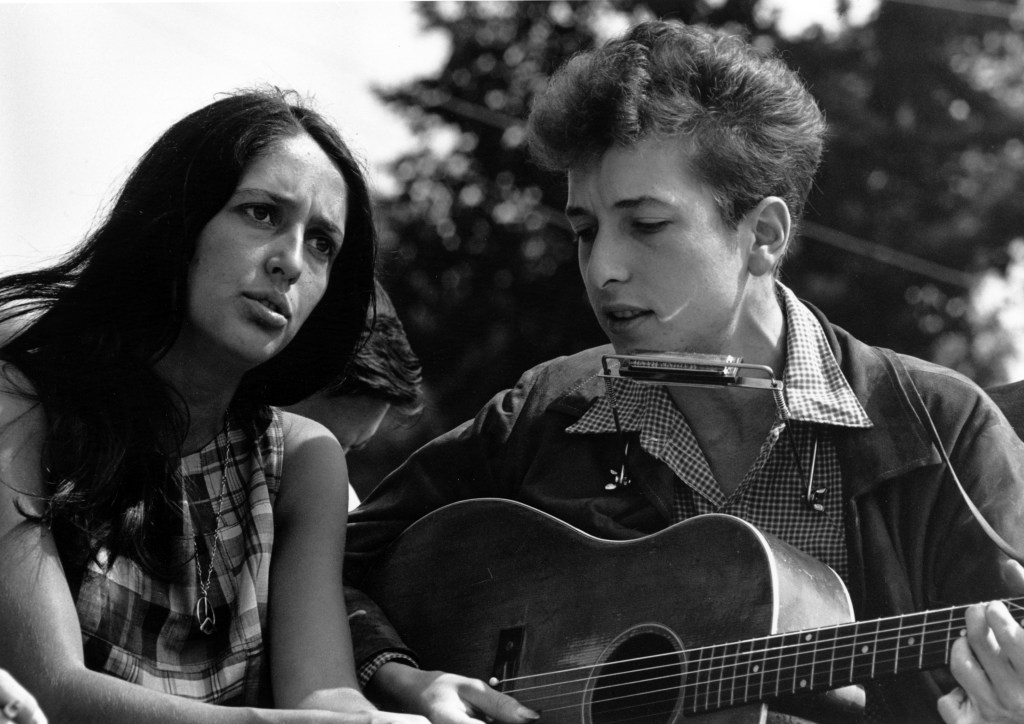

Baez cut her teeth as a singer in the Cambridge, Massachusetts folk scene of the late ‘50s, when she was enrolled in college at the Boston University School Of Drama. She was signed to Vanguard Records in 1960, and soon became an international sensation. Early in her career, she met Bob Dylan, who at the time was hailed as the second coming of Woody Guthrie. Baez helped introduce the young Dylan to the world at large, sharing the stage with him and recording his songs.

Throughout her career, Baez has primarily been known as an interpreter of other people’s work. However, many of her own compositions, such as “Diamonds And Rust” and “Here’s To You,” reveal her depth as a lyricist and songwriter.

Baez continues to record and tour – and she looks and sounds great. Her last album, Day After Tomorrow, was produced by Steve Earle, and features songs by Elvis Costello, Gillian Welch, Tom Waits and others.

Do you remember the process of writing that song? Was that one that came in a burst or did you cultivate it for a while?

As this story is being written, Baez is set to embark upon a tour of France, followed by another tour with Kris Kristofferson, whom she first met at the Isle of Wight festival years ago. We spoke with the singer about Dylan, songwriting, and the state of American politics.

You’re known primarily for the songs you cover. Was there ever a point when you considered writing more of your material?

I haven’t written for the last 20 years. I think the poetry in my songs is really good. And I think the melodies are really good. And I think the only trick with my songs is that they’re not the kind of songs that people are urged to cover because they’re more personal. I write them more personal; it’s like reading a poetry book.

“Diamonds And Rust,” which is one of your more well-known compositions, fits more into that personal category.

Yeah, and it’s the only one that crossed over from very personal to being acknowledged in a very big way.

Well, it’s funny because I was writing it and it had nothing to do with what it turned out to be [Ed note: It’s widely believed to be about Bob Dylan]. I don’t remember what it is, but I think I was writing a song. It was literally interrupted by a phone call, and it just took another curve and it came out to be what it was.

Your history with Bob Dylan is a significant part of your legacy as an artist, which I imagine has been a double-edged sword for you. Was there ever a point where you considered not covering Dylan songs in concert?

His songs are so amazing. Even through his dormant period, for me, his songs can stand on their own. They’re the best.

When you play the Dylan songs live, does your relationship to them feel more aesthetic than personal?

Well, yeah. I haven’t seen him at a lot of them [my concerts], but he was very sweet in my documentary. So, I think the playing field’s level, and the songs are what they are.