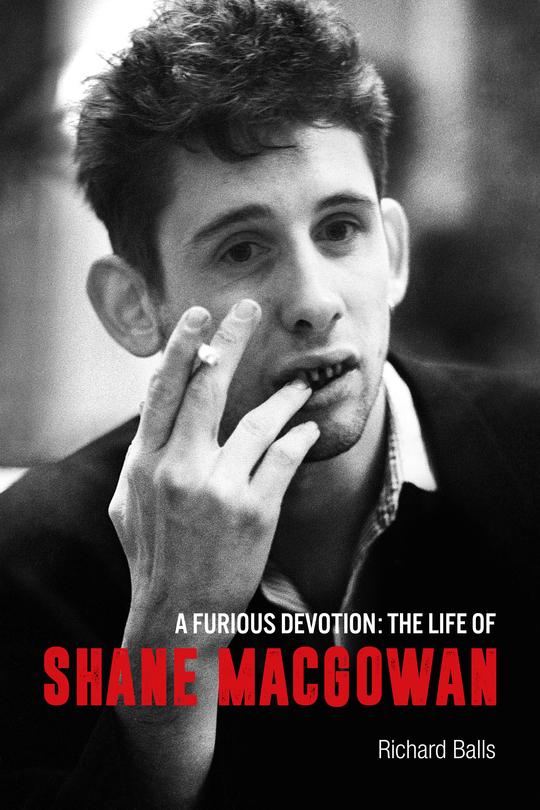

Writing the biography of the man best known for marrying traditional Irish music with British punk — a sound once described by concertina player Noel Hill of the band Planxty as a “terrible abortion” of Irish music — was never going to be easy. To further complicate the matter, Shane MacGowan’s hatred of interviews is almost as notorious as his long and sophisticated affair with drugs and alcohol. Such is punk.

When it comes to the story of MacGowan’s life, it has never been about “just the facts.” However, an attempt has now been made. A Furious Devotion: The Life of Shane MacGowan by British journalist Richard Balls serves up the most thorough account of the man — and myth — to date. In a nearly 400-page biography, out Nov. 18 in the U.S., Balls has attempted through extensive interviews and research to do what has proved so difficult through the years — to parse where the facts end and the myth begins. “Some of these never get resolved and probably never will be, but I am determined not to give up in my quest to sort the myths from the truths and better understand this shy and complex man,” Balls writes.

The son of Irish émigré parents, MacGowan was born and raised in England and spent childhood summers and holidays in rural County Tipperary, Ireland, with his mother’s extended family of staunch Irish republicans. Now residing in Dublin, he still speaks with an English accent, but maintains that he is Irish, for it was those experiences in Ireland that MacGowan says formed his musical and spiritual core. Some of the first traditionalists to hear the Pogues amalgamations might have been shocked, even appalled, but other icons of traditional Irish music such as the Dubliners and Christy Moore understood the power of MacGowan’s writing early on.